Amyloid-β Proteins Differ Between Alzheimer’s Disease Subtypes

What’s the science?

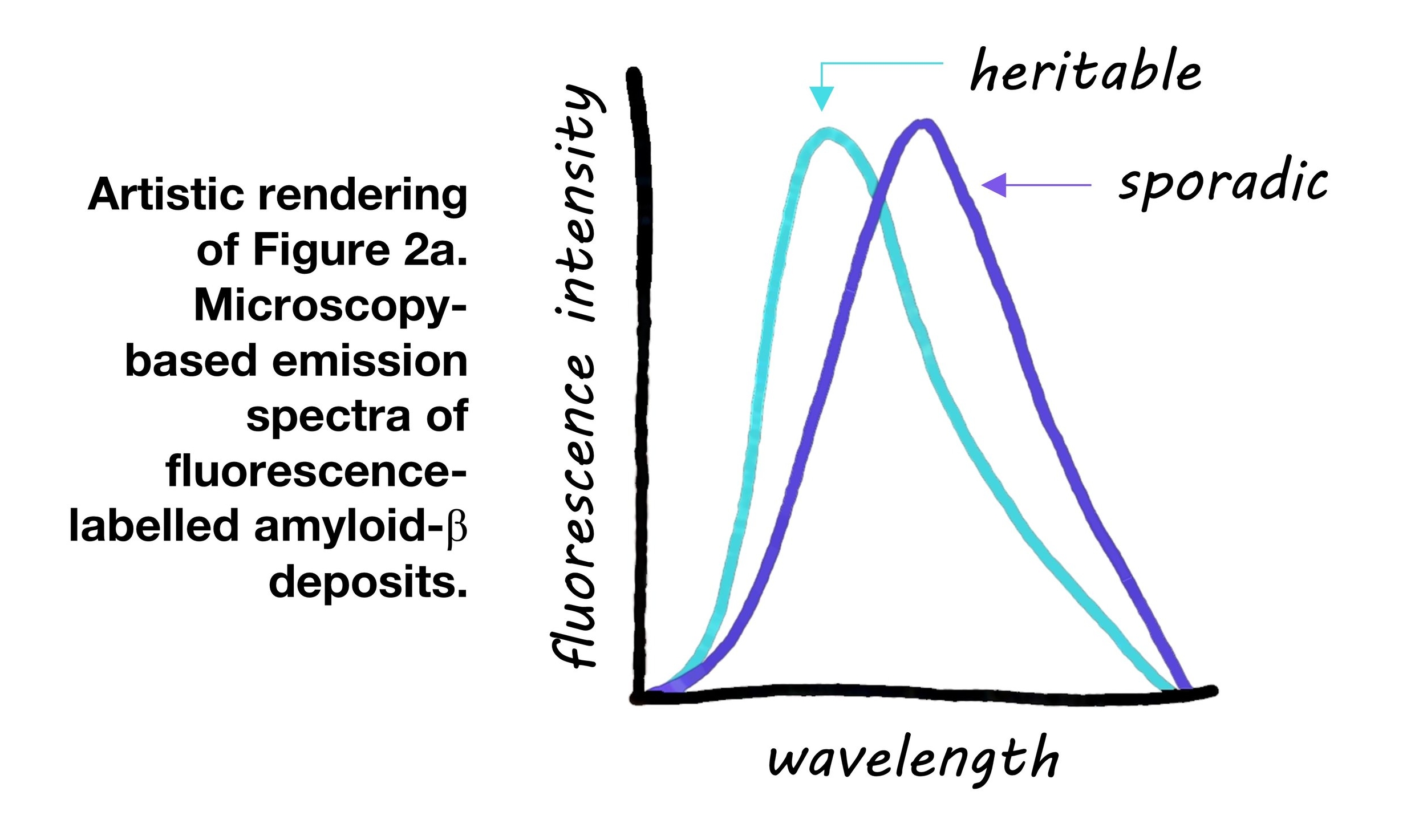

Alzheimer’s disease can be genetically inherited (familial/heritable) or sporadic. A key feature of the disease is the build up of amyloid-β proteins in the brain. A mutant form of amyloid-β is found in heritable Alzheimer’s disease, and is thought to cause the misfolding of normal amyloid-β proteins, leading to a more rapid build up. Recently in PNAS, Condello and colleagues probed the structure of different conformations or strains of amyloid-β proteins, to see whether they differ between heritable and sporadic Alzheimer’s.

How did they do it?

They performed confocal spectral imaging using three fluorescent dyes that bind to amyloid protein and are sensitive to protein structure in mouse and human brains. Different dyes bind differently to distinct protein conformations. In mice, they combined mutated and non-mutated amyloid-β, to test whether the mutated form could cause protein misfolding.

What did they find?

The heritable and sporadic amyloid-β plaques exhibited different fluorescence intensities after staining with the three dyes, meaning they could be differentiated. The fluorescence emission spectra also differed between disease types, suggesting different protein conformations. In mice, when mutated and non-mutated amyloid-β were mixed, the mutated amyloid-β acted as a template allowing the normal amyloid-β to misfold.

What’s the impact?

This is the first study to use this fluorescence microscopy technique to assess different strains of amyloid-β. The different protein structure in these amyloid-β strains could help to explain differences in the rate of disease progression, for example between familial Alzheimer’s disease compared to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the differences in protein structure between these amyloid strains may help clarify how they cause other proteins to misfold and the disease to spread.

C. Condello et al., Structural heterogeneity and intersubject variability of Aβ in familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. PNAS. 115(4) (2018).