Accelerating Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Treatment for Depression

What's the science?

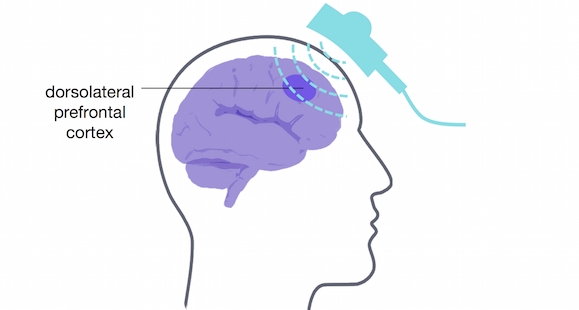

Thirty percent of people with depression are resistant to treatments like anti-depressant medication or psychotherapy. Some people with treatment-resistant depression respond to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) treatment. This technique involves inducing a magnetic field using pulses from a magnetic coil in a device resting on the scalp. However, it might take a patient many weeks of rTMS to see mood improvement, so having a faster acting treatment for those with severe depression is optimal. This week in Neuropsychopharmacology, Fitzgerald and colleagues tested a new ‘accelerated rTMS’ paradigm, to see if the same effects could be achieved faster.

How did they do it?

The authors conducted a randomised controlled trial, in which adults with depression received 63 00 rTMS pulses in total over the course of several rTMS sessions. Pulses were targeted at the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, known to be involved in emotion regulation. Fifty-eight adults followed the accelerated schedule: They received 3 treatments per day, for 3 days the first week, 3 treatments over 2 days the second week, and 3 treatments in one day the third week. Fifty-seven adults followed a standard schedule (not accelerated): one treatment per day, 5 days a week, for 4 weeks. They measured depression scores 1, 2, 3, 4, and 8 weeks after treatment.

What did they find?

Depression scores slowly decreased over the 8-week period in both the accelerated and standard treatment groups. The accelerated treatment did not appear to improve mood faster than the standard treatment, and participants in the accelerated group were more likely to experience discomfort such as headache. There were no differences in the efficacy of the accelerated treatment versus the standard treatment, indicating the accelerated treatment worked just as well as the standard treatment.

What's the impact?

This is the first randomised controlled trial to test whether accelerated rTMS could be used as a treatment for depression. This study clarifies the effectiveness of accelerated rTMS as a treatment for depression. Accelerated rTMS might be a viable option for individuals with depression who cannot commit to long periods of daily rTMS treatment. Depression comes in many different forms, so determining which treatments work best for which patients, and their potential side effects, is critical for treatment optimization.

Reach out to study author Dr. Paul Fitzgerald on Twitter @PBFitzgerald

P.B. Fitzgerald et al., Accelerated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2018). Access the original scientific publication here.