Transcriptomic Changes in Cellular Communities In the Brain Contributes to Alzheimer’s Disease

Post by Soumilee Chaudhuri

The takeaway

Major brain cell types — neurons, oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells, etc. — individually and synergistically contribute towards molecular changes seen in the aging human brain in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). A high-resolution transcriptomic map in the aging human brain unraveled 1) diverse cell populations associated with AD and 2) how networks of cellular communities coordinate to alter biological pathways, ultimately leading to AD.

What's the science?

Alzheimer’s Disease is an irreversible, neurodegenerative illness, with a complex pathophysiology. Amongst many unknowns in the molecular mechanisms of AD, is the specific contribution of major cell types in the aging brain and how this might trigger AD-related dementia. Even so, knowledge of the contribution of different brain cells in AD pathogenesis has advanced over the last decade due to the advent of high-resolution technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing. We know that perturbation in transcriptomes (i.e., full range of mRNA molecules produced) of major brain cell types and subtypes like excitatory and inhibitory neurons, oligodendrocytes or microglia for example, synergize to cause events that lead to molecular changes seen in AD. However, we do not know the specific contributions of each cell subtype to this disease due to limited sample size and a lack of robust and sensitive technologies powerful enough to capture interindividual as well as cell-specific diversity in AD brain. This week in Nature Neuroscience, Dr. Cain and colleagues unravel the distinct cellular architecture of the aging brain prefrontal cortex in AD as well as how cells interact, using combined bulk and single cell RNA sequencing analyses and novel bioinformatics pipelines.

How did they do it?

The authors used a powerful approach to get insights about coordinated multicellular communities in the AD brain. They used a) integrative transcriptomics (bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing) as well as b) a robust analytical approach (CellMod: a deconvolution tool that allows estimation and projection of single cellular landscapes from a limited set of individuals to a higher number of individuals). The authors used single-cell data from 24 individuals from the ROSMAP cohort to generate a cellular map of the aging Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) brain region, and used that as input to their novel CellMod deconvolution algorithm to estimate cellular compositions in an independent set of 638 individuals with bulk RNAseq data. Then, network analysis within this model revealed cellular sets and subsets and interacting cellular communities across individuals with AD vs. controls; and advanced statistical modeling associated known AD traits and risk factors to these identified cell subsets and communities across the case (AD) vs control (no AD) groups.

What did they find?

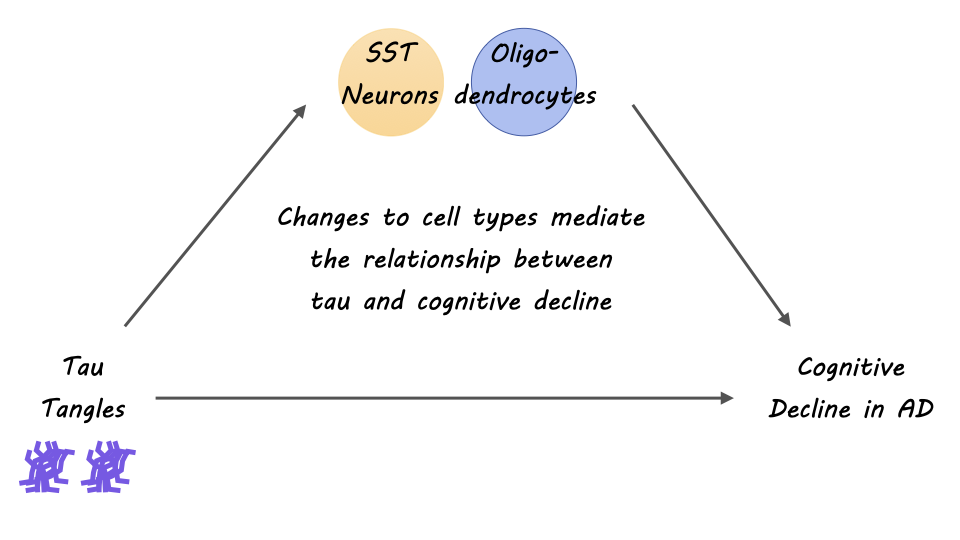

The authors identified specific subpopulations of cells associated with AD pathophysiology. Primarily, the authors discovered oligodendrocyte transcriptional pathways and a downregulation in somatostatin-producing neurons (SST neurons) as perturbed in AD pathogenesis. From the innovative cellular map of the neocortex that the authors constructed, they found interesting insights about oligodendrocyte diversity and interactions, implicating oligodendrocytes —the myelinating cells of the brain — as a strong cellular contributor to AD. Further, they identified that oligodendrocyte expression from both positive (Oli.4) and negative oligodendrocyte (Oli.1) cells was strongly associated with tau pathology and cognitive decline in AD. Multiple shared pathways within cellular communities were identified and related to known risk factors of AD, as a way of validating that AD indeed, is a pathophysiologic process with multiple interacting cell types. Overall, the findings of this study pinpoint the importance of approaching our understanding of AD through a lens of interacting multicellular communities and networks.

What's the impact?

This study is the first to show that cell specific as well as coordinated cellular and sub-cellular interactions in the aging brain may contribute to a diseased microenvironment in AD. Additionally, the authors find evidence of the contribution of communities of oligodendrocytes to cognitive decline and tau burden in Alzheimer’s Disease. The result of this study extends research on cellular and subcellular heterogeneity in the diseased aging brain and helps to inform therapeutic targets for AD and dementia.