Age-Related Neurodegeneration in Huntington’s Disease is Associated with Impaired Autophagy

Post by Leanna Kalinowski

The takeaway

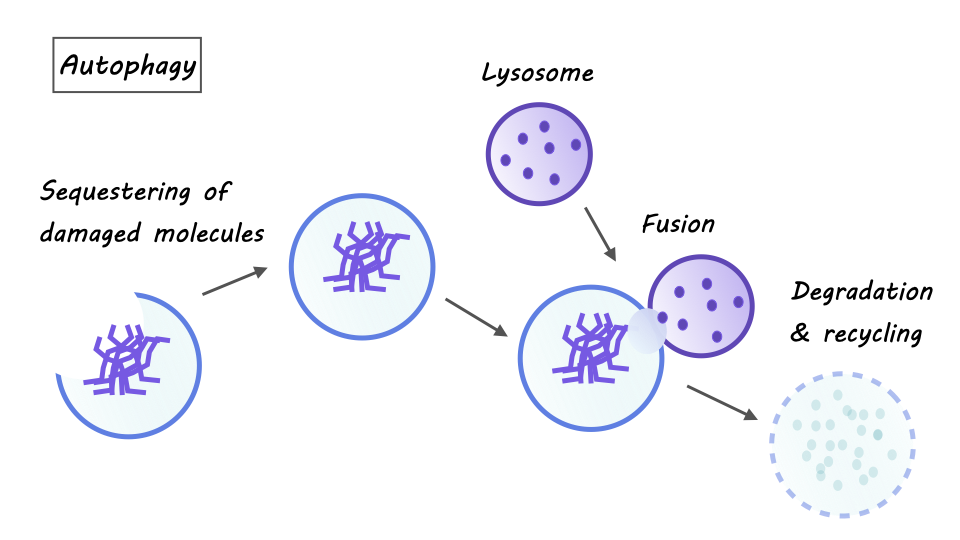

Age-related neurodegeneration in people with Huntington’s disease is associated with an inhibition of autophagy in neurons, which is when old cells are recycled in order to regenerate new cells.

What's the science?

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by uncontrollable movements, emotional and behavioral problems, and cognitive decline. Symptoms of HD progressively get worse over time, however, it is unclear how getting older drives the onset of neurodegeneration in people with HD. This week in Nature Neuroscience, Oh and colleagues examined the underlying mechanisms of age-related neurodegeneration by reprogramming cells from HD patients into medium spiny neurons.

How did they do it?

The researchers used cell reprogramming to convert fibroblasts (non-neural cells that contribute to the formation of connective tissue) into medium spiny neurons (MSNs), which are the primary neurons that degenerate in people with HD. The reprogrammed cells were from three groups of patients: (1) patients with HD who show symptoms (“symptomatic HD MSNs”), (2) patients with HD who do not yet show symptoms (“pre-symptomatic HD MSNs”), and (3) age-matched patients who do not have HD (“controls”).

After reprogramming these cells, they tested the hypothesis that symptomatic and pre-symptomatic MSNs exhibit differences in autophagy, which is the body’s process for recycling damaged cells to regenerate new ones. They measured several markers of autophagy (e.g., the number of autophagosomes) and compared them across each group of MSNs. Then, to directly test the impacts of autophagy on HD symptomology, they treated cells with substances to inhibit or enhance autophagy and measured subsequent levels of MSN degeneration.

They then investigated epigenetic mechanisms that underlie differences in gene expression between pre-symptomatic and symptomatic HD MSNs. First, they conducted chromatin accessibility profiling, which measures how tightly DNA is packed into chromatin and determines how accessible it is for gene transcription (the tighter the DNA is packed, the less accessible it is for transcription). They then probed group differences even further by measuring microRNAs (miRNAs), which inhibit gene expression by preventing translation.

What did they find?

First, they found that, relative to controls and pre-symptomatic HD MSNs, symptomatic HD MSNs have lower levels of autophagy markers. This suggests that autophagy is inhibited in patients with symptomatic HD. Next, they found that inhibiting autophagy in pre-symptomatic HD MSNs increases the degeneration of these cells while enhancing autophagy in symptomatic HD MSNs decreases the degeneration of these cells. This highlights an association between the inhibition of autophagy in patients with HD and subsequent neurodegeneration.

When evaluating the epigenetic mechanisms of these differences, the researchers found that the genes with reduced chromatin accessibility in symptomatic HD MSNs are genes that are involved in autophagy (e.g., ATG16L1, ATG10). This means that these autophagy genes are more difficult to transcribe in symptomatic HD MSNs, leading to an inhibition of autophagy. These effects are driven by differences in miR-29b-3p, which is an miRNA that inhibits autophagy and promotes the degeneration of MSNs.

What's the impact?

Taken together, these results provide a better understanding of what drives age-related neurodegeneration in HD. Specifically, an increase in miR-29b-3p promotes neurodegeneration by impairing autophagy in patients with symptomatic HD. Results from this study may provide an avenue for the development of therapeutics to slow or even reverse the progression of HD.