Going Beyond the Diagnosis: What it Means to be “Transdiagnostic”

Post by Anastasia Sares

A diagnosis isn’t the whole story?

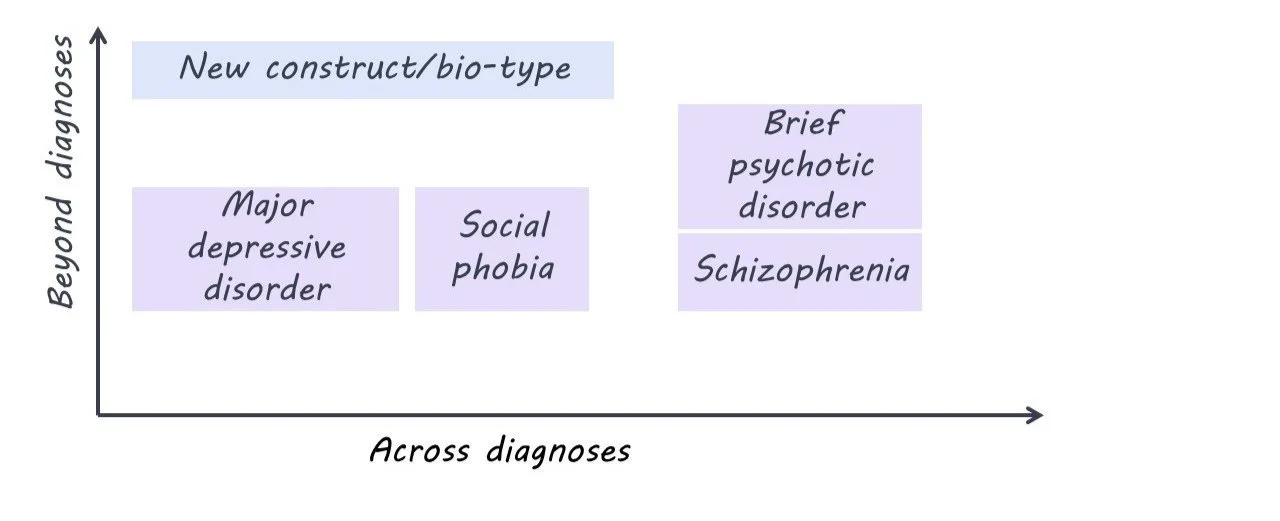

“Transdiagnostic research” is a current buzzword in psychiatry. It comes from the prefix “trans,” meaning through/across or beyond, and “diagnostic” meaning a medical category, so transdiagnostic means “across or beyond diagnosis”. The current world of psychiatry is dominated by the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and ICD (International Classification of Diseases), which defines the symptom criteria for conditions like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, eating disorders, personality disorders, and psychotic disorders. If you’ve ever taken a psychology class, this is likely the model you’ve been taught.

However, there are some problems with this system. First, there is a high amount of variability between individuals with a given diagnosis - in extreme cases, two individuals with the same diagnosis may only share one or two symptoms. Second, some symptoms overlap between disorders, and comorbidities (when someone has 2 or more diagnoses simultaneously) are more common than we would expect. Third, our categories are based largely on symptoms, not on causes or effective treatments. So, some scientists and clinicians think we need to put the old categories aside and search for a new classification system.

What would transdiagnostic research and treatment look like?

To come up with a new psychiatric classification system, we would have to find a set of traits that span across current diagnostic categories. These new traits would need to do a better job of predicting a patient’s symptoms and/or their response to treatment.

For example, one study that looked at both schizophrenia and bipolar depression found three distinct “biotypes” that were spread across the two diagnoses. One biotype showed marked cognitive impairments and lowered sensory reactivity, another showed some cognitive impairment but heightened sensory reactivity, and a third group had cognitive and sensory features comparable to the non-patient group. Knowing someone’s diagnosis doesn’t help very much in predicting what their biotype is, so these biotypes could be considered transdiagnostic.

What’s new?

Transdiagnostic research is gaining momentum, with large groups of researchers combining their efforts to try and find a new classification system. However, some are critical of the recent flood of research. A systematic review by Fusar-Poli and colleagues found that only three out of the 111 studies they examined were truly transdiagnostic. Less than half of self-titled “transdiagnostic” studies compared their new classifications directly to the current gold standard diagnoses, and when they did, the transdiagnostic approach often performed no differently than the current diagnosis-based approach. Twenty percent of the studies were not transdiagnostic at all. The authors came up with guidelines for future transdiagnostic research to guide the growing field.

What's the bottom line?

It’s obvious that the current diagnostic system in psychiatry is imperfect, but it’s the best we have so far. While there are some good examples of transdiagnostic research out there, the field needs to be rigorous and insightful if it ever hopes to replace the DSM and ICD.

References +

Dalgleish, T., Black, M., Johnston, D., & Bevan, A. (2020). Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(3), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000482

Fusar‐Poli, P., Solmi, M., Brondino, N., Davies, C., Chae, C., Politi, P., Borgwardt, S., Lawrie, S. M., Parnas, J., & McGuire, P. (2019). Transdiagnostic psychiatry: A systematic review. World Psychiatry, 18(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20631

Clementz, B. A., Parker, D. A., Trotti, R. L., McDowell, J. E., Keedy, S. K., Keshavan, M. S., Pearlson, G. D., Gershon, E. S., Ivleva, E. I., Huang, L.-Y., Hill, S. K., Sweeney, J. A., Thomas, O., Hudgens-Haney, M., Gibbons, R. D., & Tamminga, C. A. (2022). Psychosis Biotypes: Replication and Validation from the B-SNIP Consortium. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 48(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbab090