Amyloid Versus Tau Proteins in the Path to Alzheimer’s Disease

Post by Anastasia Sares

The takeaway

The two main hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain are plaques, made from proteins called amyloid-beta, and neurofibrillary tangles, made from proteins called tau. Brain activity and performance on memory tasks depend on the levels of both of these proteins in the brain, supporting the idea that amyloid is related to disease onset, while tau is related to disease progression.

What's the science?

In recent years, the field of Alzheimer’s research has hit a wall. Both amyloid and tau proteins are correlated with having the disease, but many researchers had guessed that amyloid proteins were the key, and that tau tangles were just a downstream effect. Some animal models of Alzheimer’s were created so that they naturally over-produced amyloid, which seemed to recreate the disease state. From work on these animals, treatments were developed that targeted only amyloid, but when these treatments were tried on humans in clinical trials, they didn’t work as well as people hoped. Now, researchers are re-examining the role of tau proteins in Alzheimer’s. This week in Brain, Düzel and colleagues showed how amyloid and tau status can interact in humans without Alzheimer’s dementia, affecting memory and brain activity.

How did they do it?

Participants gave samples of cerebrospinal fluid (the fluid that bathes the brain and central nervous system) so that the researchers could determine the amount of amyloid and tau proteins present in each person. Their brain activity was also recorded with MRI while they performed a memory test about recognizing familiar scenes. There were three groups of participants: people with mild cognitive impairment but without Alzheimer’s disease, people who complained of cognitive decline but nevertheless had a good memory, and healthy controls. With this sample, the researchers were able to get a variety of levels of amyloid and tau, both in individuals with cognitive decline and those without.

What did they find?

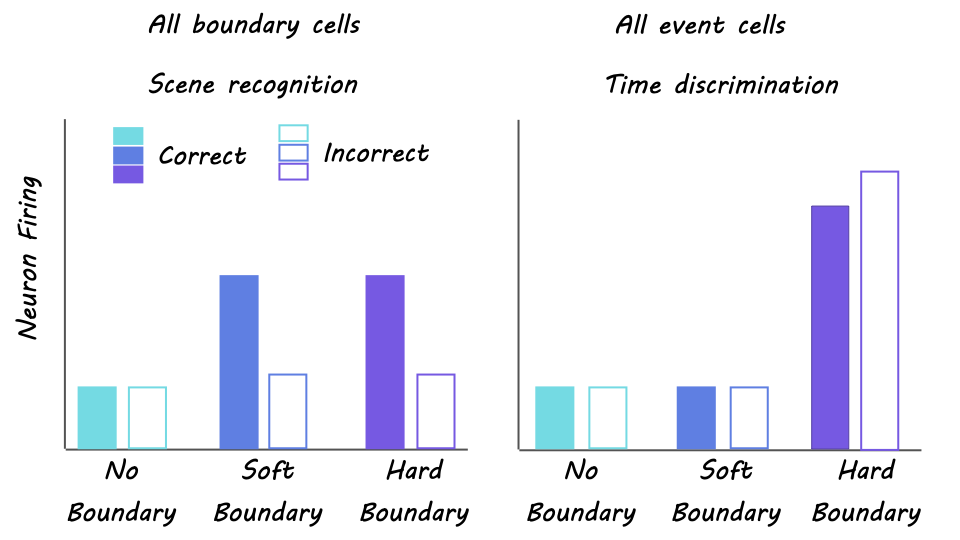

The researchers found that both memory performance and brain activity were predicted by an interaction between amyloid and tau. In “amyloid-negative” groups, tau levels were not related to memory performance, while in “amyloid-positive” groups, tau levels were related to memory performance. This result was also consistent with a paper-and-pencil test of memory recall and held true even with different statistical corrections (for example, accounting for group, age, sex, site of testing, etc.). This same interaction also showed up in brain activity during the tasks, specifically in the hippocampus and surrounding entorhinal cortex, key brain regions for forming new memories and recognizing what is familiar versus what is new. Individuals with a well-known genetic variant (APOE4) related to Alzheimer’s did not significantly differ from those without this variant.

What's the impact?

The findings of this study will help researchers in the field of Alzheimer’s to decide between competing theories of the disease, one of which is an “amyloid x tau” model. Once we have a correct understanding of the cause of Alzheimer’s in humans, we can look for treatments much more effectively.