Deliberate Errors Enhance Learning

Post by Elisa Guma

The takeaway

Deliberate errors followed by error correction may be a superior method of concept learning compared to errorless learning, particularly in low-stakes contexts.

What's the science?

Error commission is an intrinsic part of the learning process, but one that is typically avoided. Interestingly, some empirical work has suggested that making errors can enhance learning in low-stakes contexts. More specifically, there may be learning benefits from deliberately committing and correcting errors even when one already knows the correct answer, as opposed to avoiding errors—referred to as the derring effect. This week in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Wong, and Lim investigated whether deliberate erring improves concept learning.

How did they do it?

To experimentally test the derring effect, the authors conducted three experiments. In Experiment 1, the authors investigated whether making deliberate errors would enhance the learning of scientific term-definition concepts compared to errorless learning. Participants were asked to learn unfamiliar concepts and told to either error-cancel (deliberate erring in the definition), error-correct (deliberate erring with correction), or to copy the correct definition twice (errorless learning; control condition).

An example of a deliberate conceptual error in the error-cancel condition for the concept: “Cocktail party effect is the selective enhancement of attention to filter out distractions,” is: “Cocktail party effect is the selective enhancement of attention in making sense of distractions.” In the error-correction condition, participants additionally corrected their deliberate error by writing down the actual definition, and in the copy condition, participants wrote down the term-definition concept exactly as it was presented, then copied the key ideas in each concept again.

To assess whether the benefits observed in Experiment 1 were due to the generation of novel responses, the authors performed Experiment 2. The control group elaborated on each concept by generating an alternative conceptually correct definition, then wrote down the actual one (concept-synonym condition). For example, “Cocktail party effect is the increased focus on a particular object (selective enhancement of attention) to filter out distractions.”

Finally, to rule out the possibility that the deliberate erring advantage could be due to more elaboration, the authors ran Experiment 3 with a control group where participants generated a specific example of each concept after writing down the correct definition (concept-example condition). For example, “Cocktail party effect is the selective enhancement of attention to filter out distractions. At a noisy party, Kate was able to focus on what her partner was saying while ignoring other people’s conversations.”

In all experiments, following the learning phase, participants were tested on the definitions they learned. Each response was scored either as correct or incorrect, and errors were also coded into 4 categories: (a) commission errors (i.e., inadequate or incorrect responses that were different from participants’ initial deliberate errors), (b) omission errors (i.e., no response), (c) confusion errors (i.e., responses that gave the definition for another studied concept term instead), and (d) intrusion errors (i.e., in the errorful conditions only, responses that repeated the same deliberate errors that participants had committed during initial study).

What did they find?

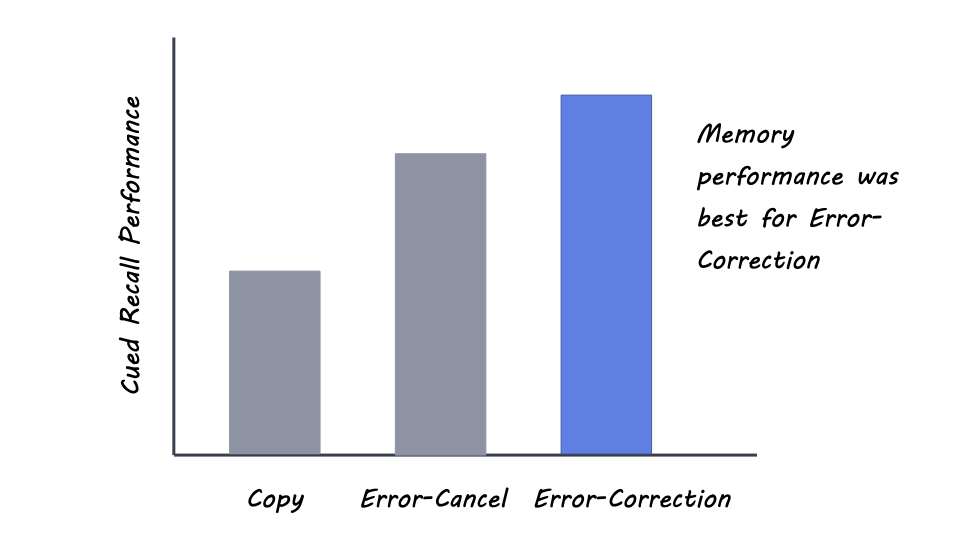

In Experiment 1, the authors found that learners performed better when they had deliberately generated incorrect definitions of scientific concepts compared to errorless copying of the definitions, supporting the derring effect. This advantage was even greater when learners were told to correct their deliberate errors. Interestingly, most of the errors at test were commission errors and not intrusion errors, indicating that deliberate erring did not interfere with test performance.

In Experiment 2, the error-cancel and error-correction methods still outperformed the concept-synonym method, providing further evidence for the advantage of deliberate erring even over actively generating alternative correct responses. Finally, in Experiment 3, the authors still found that the error-correction method outperformed the concept-example method, despite the latter being bolstered by a higher degree of elaboration.

What's the impact?

The findings in this study provide compelling evidence for the benefit of deliberate erring in low-stakes learning environments, particularly when one's errors are corrected. This method of learning may improve the processing of the correction after an error has been deliberately made, supporting better memory performance. Future work may investigate the effects of different kinds of deliberate errors across a range of educational materials. For example, teachers could integrate deliberate erring in homework assignments to help students learn better.