Stroke Disrupts Brain Network Dynamics

Post by Anna Cranston

What's the science?

Post-stroke cognitive decline is described as the onset of memory loss and cognitive dysfunction following an ischemic stroke. However, smaller infarcts can also lead to milder cognitive deficits such as impaired attention and the inability to concentrate. Smaller infarcts can also occur in brain regions not typically associated with cognitive function. The underlying physiology of this phenomenon, known as post-stroke acute dysexecutive syndrome (PSADES), remains unclear. This week in PNAS, Marsh and colleagues used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to investigate differential activation patterns following minor strokes in patients exhibiting PSADES to determine the underlying pathophysiology.

How did they do it?

The authors recruited a group of patients who had recently been hospitalized with MRI evidence of a small acute ischemic stroke. Due to the small size of the lesion, patients appeared almost normal, without any problems moving or speaking. Prior to study participation, all patients underwent comprehensive neurological examinations and cognitive screening using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). The authors also selected age-matched individuals with no prior history of stroke as a control group. They used MEG, a technique used to map brain activity, via the magnetic fields the brain generates, to determine differences in cerebral activation patterns between stroke and control groups. They recorded MEG activity during the completion of a visual comprehension task involving picture-word matching. Analysis of MEG activity at selected time points, known as epochs, were analyzed using a specific time-frequency analysis known as cluster-based permutation. The authors also used source localization analysis to map the spatiotemporal activity of each patient’s brain and then targeted their analysis to recorded activity from the occipital lobe, fusiform gyrus, and lateral temporal lobe, given their importance in visual recognition and language processing.

What did they find?

The authors found that minor stroke patients scored significantly lower on cognitive tests compared to control patients. In addition, they displayed reaction times twice as long as those of controls during the visual comprehension tasks. Although differences in reaction times may seem subtle, they are clinically significant in the context of being able to respond or shift attention back and forth quickly during conversations. Using MEG analysis, the authors also identified group differences in activation patterns within the visual cortex, fusiform gyrus, and lateral temporal lobe. They found that stroke patients exhibited a significantly different activation pattern in the brain in response to visual stimuli. Specifically, stroke patients exhibited brain responses of smaller amplitude with less temporally distinct activation peaks following a minor infarct. These differences in activation were found to be more prominent in the fusiform gyrus and lateral temporal lobe.

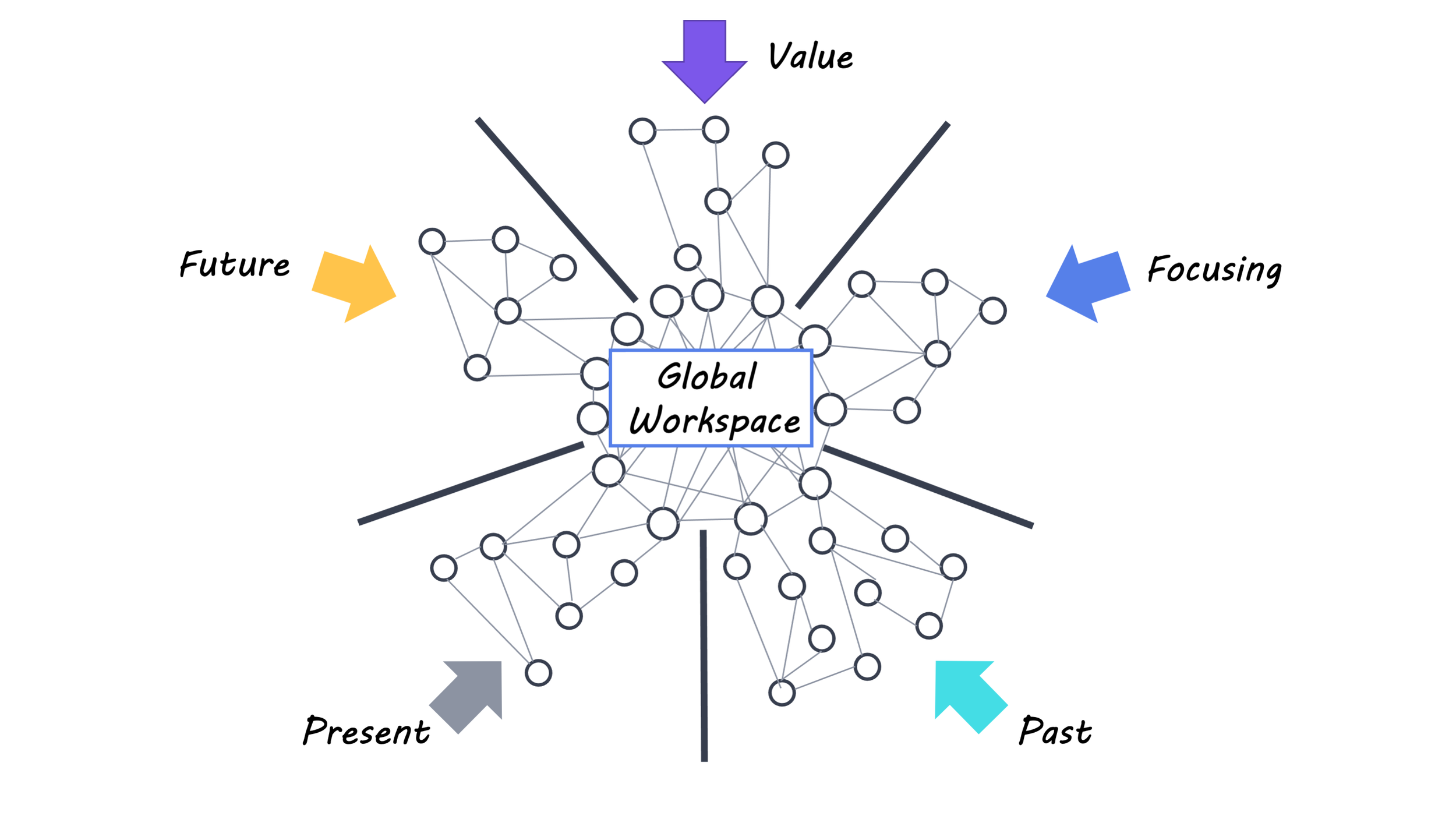

Of particular interest, each of the stroke patients tested in the study exhibited small acute infarcts in regions of the brain not typically associated with cognitive dysfunction. The activation patterns in these non-cognitive regions suggest that a disconnect in the processing loops in the brain, or network dysfunction, may be responsible for the observed PSADES symptoms in the stroke patient group. The authors also found that while control patients were able to modulate the amplitude of their brain activation in response to words, stroke patients displayed a consistently low amplitude for all stimuli. These differences remained for up to 6 months later in stroke patients, which may help to explain why patients demonstrate cognitive fatigue in the initial months after stroke.

What's the impact?

This study found that patients with minor strokes had cognitive deficits and slowed reaction times that corresponded to abnormal activation patterns of brain activity, independent of stroke location. The authors suggest that a dysregulation of brain network dynamics may be responsible for the observed long-term deficits that occur in PSADES following minor strokes. These findings highlight the importance of brain network dynamics, even in simple tasks, such as word processing. This work provides the basis for future studies to investigate the exact underpinnings of PSADES, with the hope that this can eventually be targeted for therapeutic purposes.

Marsh et al. Poststroke acute dysexecutive syndrome, a disorder resulting from minor stroke due to disruption of network dynamics. PNAS (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.