The Role of Group Identity in Social Influence

Post by Lincoln Tracy

What's the science?

Social influence refers to the change in behavior (either intentionally or unintentionally) a source (e.g. a person) causes in a target (e.g. another person). This is a broad notion that covers a range of phenomena, one aspect of which is group influence. Individual influence frequently contrasts with group influence. Such topics are normally addressed separately in introductory textbooks. Furthermore, earlier reviews have not fully explored the group identity approach to influence. This week in Annual Reviews of Psychology, Spears summarizes recent research about group identity while also reappraising classical research, aiming to provide an integrated overview of group identity in social influence.

What do we already know?

Group influence research has been heavily influenced by Deutsch and Gerard’s dual-process model, first proposed in 1955. This model identifies the two psychological needs that lead humans to conform: informational influence (the need to be right) and normative social influence (the need to be liked). While normative influence is a form of group influence, personal identity and interpersonal dynamics are implicated in normative influence. Deutsch and Gerard’s model is one of many early theories to distinguish different forms of influence. The concept of group identity had not been developed at this point. Consequently, group influence retained an element of external pressure as there was no concept of group identity to internalize this process. A theoretical shift was required to see the group as part of the self. Such a shift would allow for the possibility that true group influence may lead to private acceptance. Using network approaches to account for the spread of influence throughout a group offers some potential. But one challenge with many network models is that the process of how influence operates is not always clear, even if we can model and predict the spread of influence.

What’s new?

Research primarily focusing on the theoretical underpinnings of group identity-based influence has waned in recent times. Despite this decline, the principles underlying group identity-based influence are still sources of inspiration for not only more recent research, but also for reviewing classic findings. However, there has been an emergence of other research that has shifted focus somewhat and brings a different approach to considering social norms. A major theoretical development occurred following the differentiation of descriptive and injunctive norms (behaviours everyone else is doing and behaviours you feel you are supposed to do, respectively). These concepts have been widely adopted by the social norm literature, and research from theorists of morality have made the case that as group identity frames values and prescribes norms, group identity also implies group morality. This notion prefaces a wide-ranging discussion of the association between norms, motivation, and morality. This discussion confirms that there is no “generic” norm, but that the relevant group priority is flexible. This resonates with the argument that group identities are variable and contested, rather than dominant or assigned. Prototypicality, group identification, salience and identity threat, social isolation, and anonymity are identified as moderators of group identify-based influence.

What’s the bottom line?

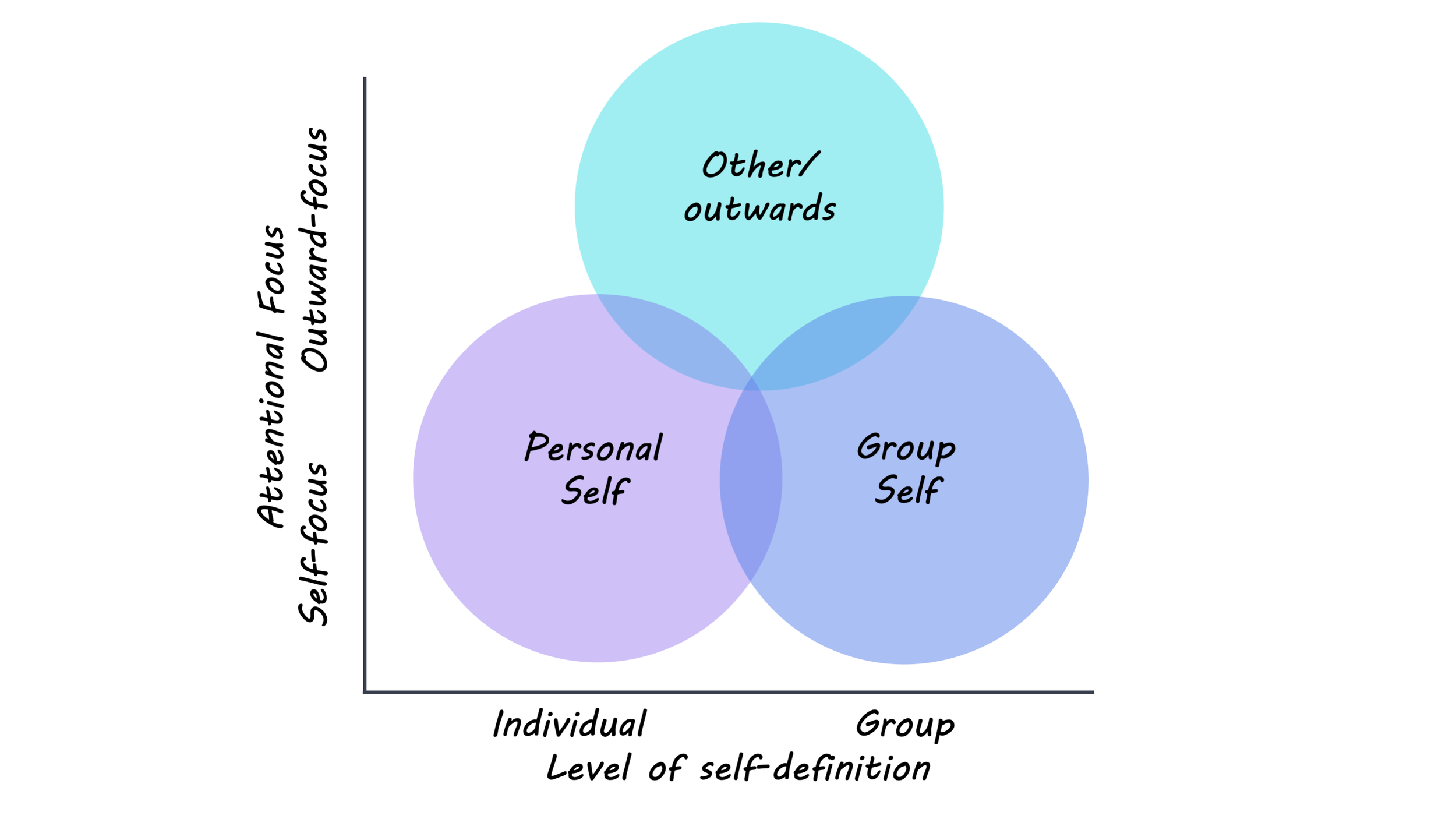

Spears provides a case for group identity-based social influence and argues that this may be more persuasive than first thought. Group identity can be distinguished from other forms of social and group influence. Group identity serves as the foundation for much of our being and behavior. Further exploration of the relationships between the personal self, the group self, and the outwards facing self is required.

Spears. Social influence and group identity. Annual Reviews of Psychology. Access the original scientific publication here.