Loneliness Distorts Neural Representations of Social Connection

Post by Cody Walters

What’s the science?

Social connection is a key component of well-being. Social isolation and loneliness, on the other hand, are known to pose significant health risks. Despite the important role that social relationships play in one’s overall wellness, it remains unclear how the brain represents relationships between oneself and others and whether those representations are modified by loneliness. This week in The Journal of Neuroscience, Courtney and Meyer show that there are distinct neural representations stratified along social-closeness categories, with lonelier individuals having representational distortions between themselves and others.

How did they do it?

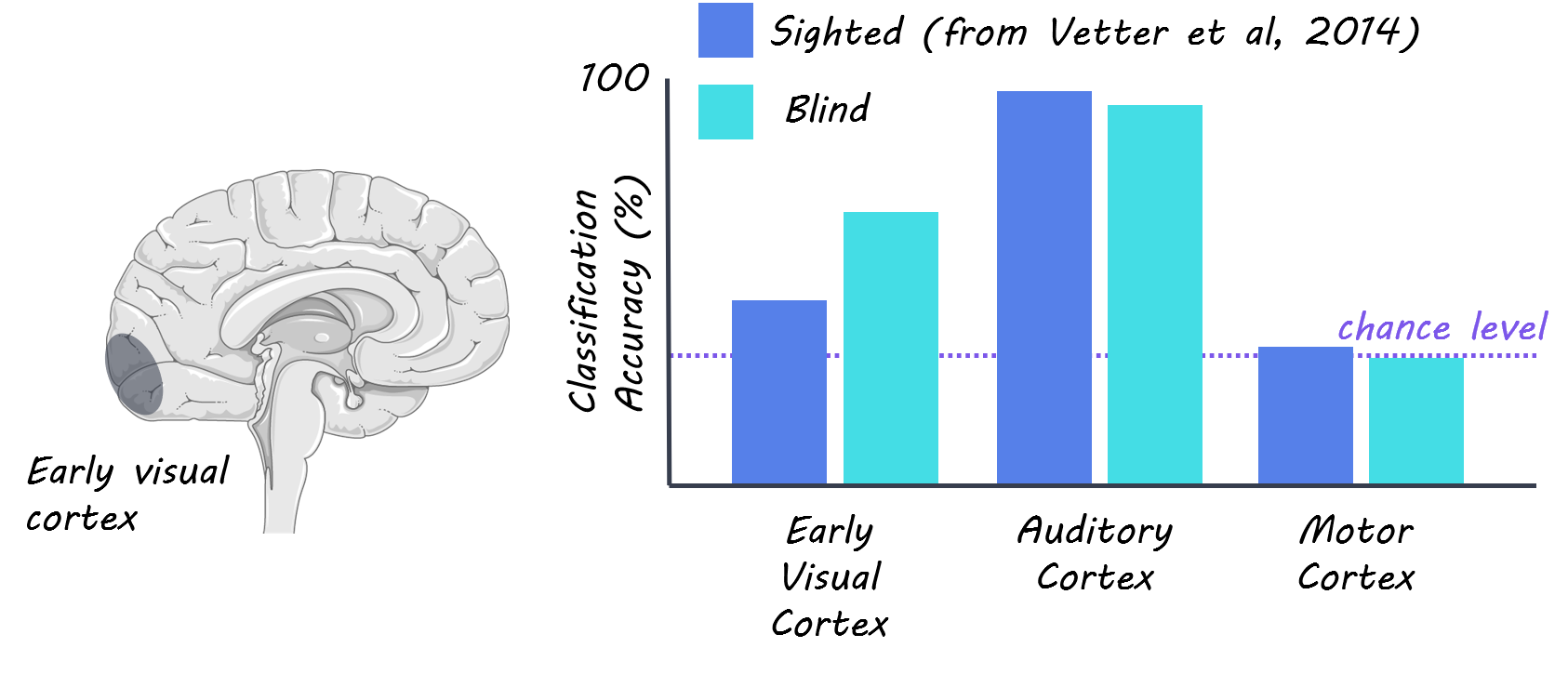

The authors used both univariate (i.e., average activity across voxels) and multivariate (i.e., multi-voxel patterns of activity; a voxel is like a 3D pixel in an image of the brain) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) analyses. Multivariate analyses typically involve training a classifier (machine learning model) to distinguish between multi-voxel activation patterns that correspond to specific stimuli. The authors used two multivariate methods: representational similarity analysis (RSA) and whole-brain searchlight analysis: RSA is a method for comparing patterns of blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) brain activity between distinct stimuli to quantify how similar (or dissimilar) they are, whereas whole-brain searchlight analysis is an approach for identifying voxelated neighborhoods that exhibit specific patterns of brain activity.

Prior to placing the participants inside the MRI scanner, the authors had participants list out and rank the names of five close others as well as five acquaintances. While in the scanner, participants fixated on a screen that displayed these target names (either their own name, one they supplied or one of five well-known celebrities) along with traits (e.g., polite, amusing, etc.). Participants then had to indicate how well the trait described that person on a scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘very much’).

What did they find?

The medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) is known to represent information about the self as well as close others, thus the authors examined the activity of a predefined MPFC region of interest. Specifically, they constructed a representational dissimilarity matrix in order to test whether there was any meaningful structure in how self-other relationships are categorized in the MPFC. The authors identified that there were three representational clusters corresponding to self, social network members (i.e., close others and acquaintances combined), and celebrities. The authors then employed a whole-brain searchlight analysis to look for other brain regions that shared a similar clustering profile as the MPFC. They found that regions commonly implicated in social cognition — the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), precuneus, middle temporal gyrus, and temporal poles — also exhibited a three-cluster structuring of self-other representations. Next, the authors investigated whether ranked closeness to the targets influenced neural responses. Restricting their analysis to the predefined MPFC region of interest, they found that mean MPFC activation linearly increased with perceived closeness to the target. The authors examined the extent to which representations of the self overlapped with representations of others. While self-other overlap did not linearly increase by target category (close others, acquaintances, and celebrities), they did find greater overlap between representations of the self and close others relative to acquaintances and celebrities. They identified the PCC/precuneus, as well as the MPFC as regions where the representations of others, were more similar to the representation corresponding to the self.

To examine whether loneliness modulated self-other representations, the authors used an established loneliness questionnaire. Between target categories, they found that the MPFC of individuals who reported higher loneliness represented adjacent (e.g., close others and acquaintances) and distal (e.g., close others and celebrities) targets as being more similar to one another. Furthermore, they found that within categories, acquaintances were represented more similarly to one another in both the MPFC and PCC of lonelier individuals. These data suggest that there is a blurring of representational similarity within and between social groups in lonely individuals. The authors also found that loneliness was negatively correlated with self-other similarity across all categories (close others, acquaintances, and celebrities) in the MPFC, whereas loneliness was positively correlated with self-other similarity across all categories in the PCC. These findings suggest that lonelier individuals might perceive others as being dissimilar from themselves owing to a lack of self-other representational similarity.

What’s the impact?

The authors provided evidence indicating how the brain might map out subjective social closeness in terms of representational similarity and how these representations are blurred and skewed in lonelier individuals. Developing a better understanding of how the brain processes interpersonal ties and how that processing is disrupted as a result of social isolation has implications for advancing our scientific understanding of happiness and well-being.

Self-other representation in the social brain reflects social connection. The Journal of Neuroscience, (2020). Access the publication here.