Exploring the Long-Term Effects of Psychedelics on the Brain

Post by Flora Moujaes

What's the science?

Psilocybin, the psychoactive compound in magic mushrooms, has recently proven an effective treatment for depression, anxiety, tobacco addiction, and alcohol use disorder. Treatment with psilocybin can have long-lasting effects: 1-3 psilocybin sessions can lead to a reduction in clinical symptoms that lasts for up to one year. We still don’t fully understand the psychological and neural mechanisms that underlie psilocybin’s therapeutic effects. Molecular studies have shown that psilocybin is a serotonin 2A/5-HT2A partial agonist, while therapeutic studies have indicated that psilocybin exerts its clinical effects by reducing negative affect and increasing positive affect. The reduction in negative affect may be linked to the amygdala, the brain region responsible for tracking the salience of the stimuli in the environment. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown that psilocybin reduces amygdala activity when viewing negative stimuli. This week in Scientific Reports, Barrett et al. use fMRI to explore the long-term effects of psilocybin on emotional and brain plasticity in order to better leverage it as a clinical tool.

How did they do it?

To explore the long-term effects of psilocybin, the researchers administered a single high dose of psilocybin (25mg/70kg) to twelve healthy volunteers in an open-label within-subjects pilot study. To investigate if psilocybin could lead to an enduring increase in positive affect and decrease in negative affect, a battery of self-report state and trait measures was completed one day before, one week after, and one month after psilocybin administration. Responses were then compared between time-points. At each time-point, in order to determine whether psilocybin could lead to an enduring change in neural response to emotional stimuli, participants also took part in an fMRI session in which they completed three emotion-processing tasks. fMRI analysis of the emotion-processing tasks focused on the amygdala as a key region of interest. Finally, to determine whether psilocybin could lead to an enduring change in brain plasticity, participants’ resting-state fMRI data were also collected at each time-point. Functional connectomes were then compared between timepoints.

What did they find?

Long-term behavioural effects of psilocybin on emotions: Behavioural measures indicated that one-week post-psilocybin there was a reduction in negative affect and an increase in positive affect. One month post-psilocybin, the reduction in negative affect returned to baseline levels, while positive affect remained elevated. Ratings of trait anxiety were also reduced one-month post-psilocybin, despite showing no significant reduction one-week post-psilocybin.

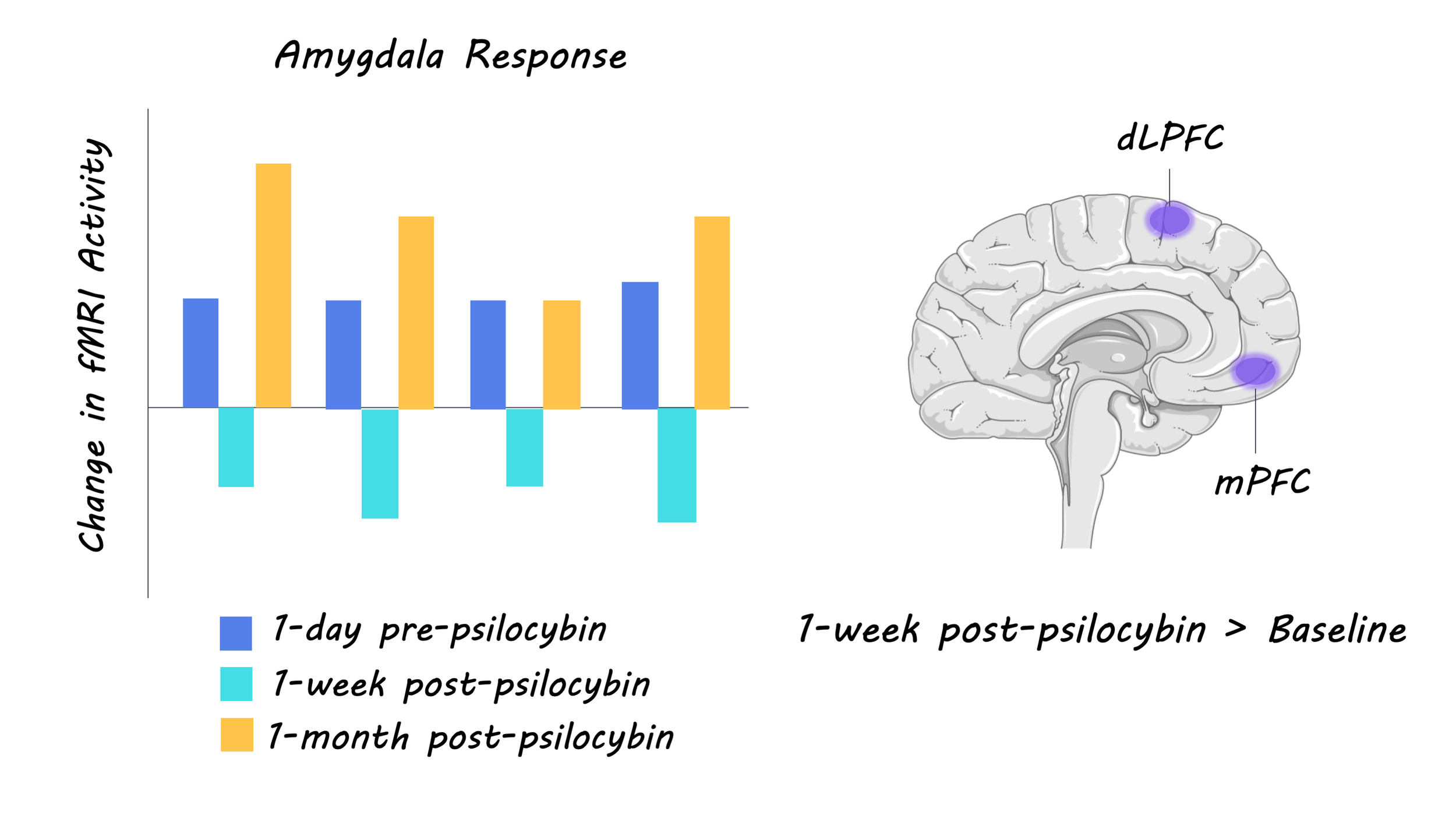

Long-term neural effects of psilocybin on emotions: Analyses of the fMRI data revealed that psilocybin led to reduced amygdala response to facial affect stimuli one-week post-psilocybin, however, this change was not sustained after one month. Overall, these results suggest that acute psilocybin administration leads to shifts in emotional affect, and the neural correlates of affective processing, which may endure one month later. fMRI data also showed that psilocybin resulted in increased dorsal lateral prefrontal and medial orbitofrontal cortex activity in response to emotionally conflicting stimuli after one week, and increased somatosensory cortex and fusiform gyrus activity in response to emotionally conflicting stimuli after one month. This indicates that psilocybin may also increase the top-down control of emotional processes, which may have a modulatory effect on the amygdala.

Long-term effects of psilocybin on brain plasticity: Global increases in functional connectivity were found both one week and one-month post-psilocybin. The increase in functional connectivity strength that was observed indiscriminately across multiple networks may reflect a domain-general cortical plasticity process that supports the observed changes in affective processing.

What's the impact?

Overall this study shows that despite the fact that the half-life of psilocybin is roughly 3 hours, psilocybin induced behavioural and neural changes were seen one-week and one-month post-psilocybin administration. This indicates that acute psilocybin may lead to a dynamic and neuroplastic period that lasts for a number of weeks, during which the neural processing of affective stimuli is altered. These findings also help explain psilocybin’s therapeutic effects: reduction of negative affect may undermine ruminative processes that contribute to depression and explain the antidepressant effects of psilocybin. Studies that utilize a larger sample size and placebo-controlled design are needed to explore this key neuroplastic period following acute psilocybin administration.

Barrett et al. Emotions and brain function are altered up to one month after a single high dose of psilocybin. Scientific Reports (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.