Activity in Insular Cortex Reflects Current and Future Physiological States

Post by Stephanie Williams

What's the science?

Information related to hunger and thirst is thought to be reflected in the ongoing activity of a region called the insular cortex. Interoception — the perception of internal bodily signals such as hunger or thirst — is critical for regulating physiological states, emotion and cognition. Models of interoceptive processing suggest that the insular cortex integrates external sensory information with internal bodily sensations (related to physiological changes like heart rate, thirst or hunger) and generates ‘interoceptive predictions’, however, the neural circuitry underlying this process remains unclear. This week in Neuron, Livneh, Lowell, Andermann and colleagues show that activity patterns in insular cortex represent current and future physiological need states.

How did they do it?

The authors used two-photon calcium imaging, circuit mapping and manipulations in mice to investigate representations of physiological need and predictions in insular cortex. For the behavioral task, the authors trained water-restricted mice to perform a visual discrimination task for water rewards. While the mice performed this task, the authors imaged neurons in layer 2/3 of insular cortex using a method involving a reflective microprism that acts as a kind of periscope. To ensure that their results were not affected by arousal, the authors monitored the pupil diameter of the mice, along with a myriad of other factors (eg. motion), which they accounted for in their analysis. The authors compared activity recorded during the behavioral task (tens of minutes) with activity imaged during rapid thirst quenching (2-5 min of continuous consumption). The authors also performed two-photon imaging of axons (N=257) that extended from the basolateral amygdala into insular cortex to better understand the pathway of cue-related information into insular cortex.

To further investigate ongoing insular cortex activity, the authors analyzed the interval between trials to see if the pattern of activity tracked the hydration state of the animal. The authors then trained a Naïve Bayes classifier — a model trained to predict whether an animal was in a thirsty or a quenched state from the activity patterns in insular cortex. They performed the same classification procedure on temporaly shuffled data and also on identity-shuffled data. They also trained the classifier on data collected in primary visual cortex and postrhinal cortex for comparison. Next, the authors mapped the circuits connecting specific types of hypothalamic neurons (eg. “hunger” or “thirst” neurons) to insular cortex neurons. They used retrograde tracers to trace neurons and then recorded light-evoked current in the labeled neurons to understand the connections between the hypothalamus, thalamus, amygdala, and insular cortex. Then, they manipulated the hypothalamic neurons to induce artificial thirst or to suppress thirst and recorded the corresponding changes in insular cortex activity. Finally, they then performed a loss of function experiment, and inhibited glutamatergic neurons in order to suppress thirst. To confirm their results in a separate dataset, the authors analyzed similar data collected under hunger versus sated state conditions, this time stimulating other hypothalamic neurons to induce artificial hunger. The authors artificial manipulation techniques allowed them to analyze both 1) cue-evoked activity related to water seeking and 2) the ongoing activity patterns related to the animal’s physiological state to artificial induction or suppression of thirst.

What did they find?

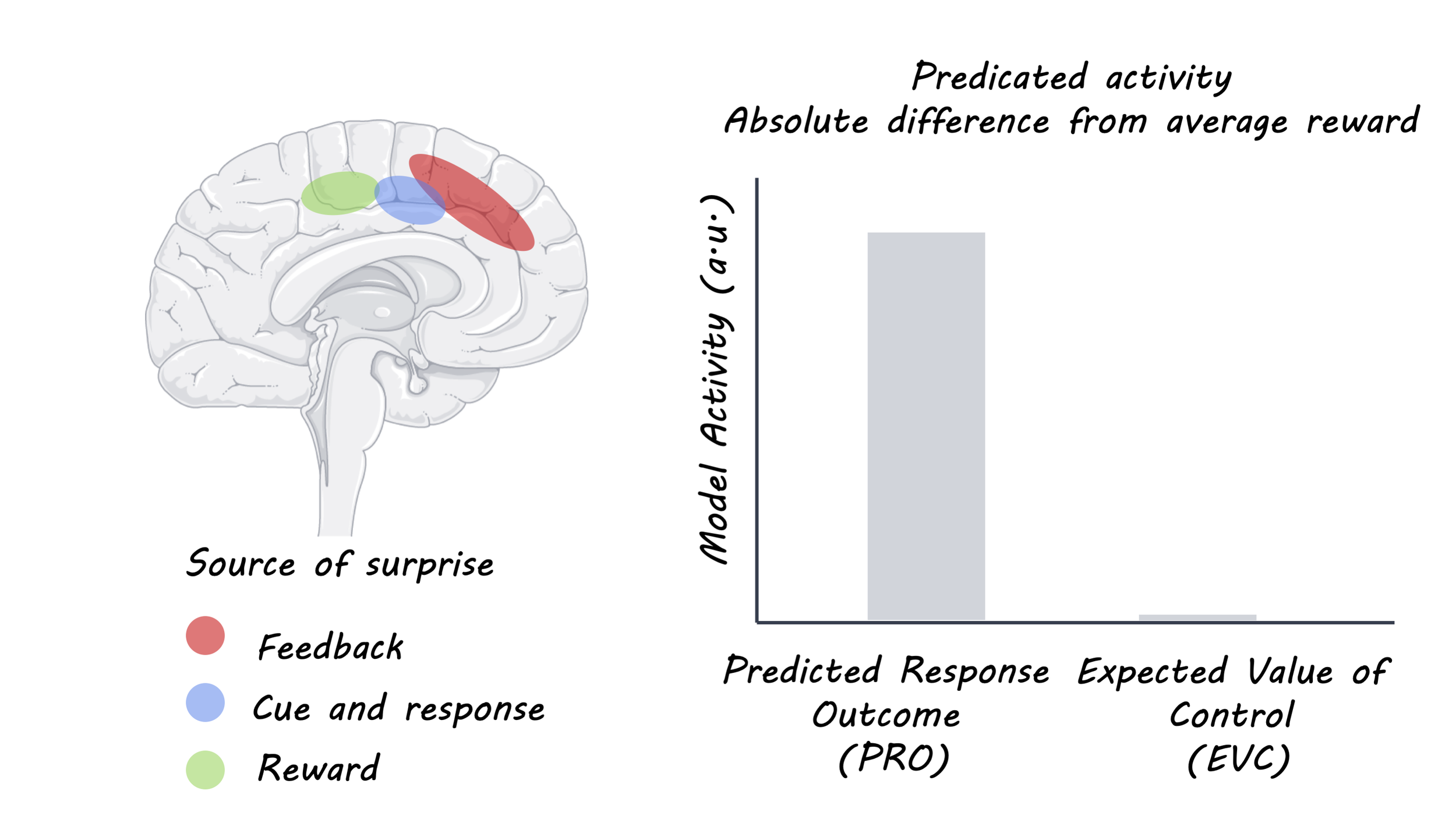

The authors found that individual insular neurons responded to 1) the visual water cue 2) the onset of licking or 3) water delivery during the behavioral task. Combined with their previous work, this result suggests that insular cortex neurons respond to learned water cues. The majority of neurons that the authors recorded from responded to the visual water cue (80%) and/or actual water consumption. They found that most cue-responsive neurons, which responded to the water cue in the thirsty state, were significantly attenuated in the quenched state. They observed this trend in data collected during both rapid thirst quenching, as well as during the behavioral task. When the authors imaged axons projecting from basolateral amygdala to insular cortex, they found that single axons responded to water cues, the onset of licking, and/or water delivery. Most of the axons they recorded from responded to the water cue or water reward, while others responded to visual cues. When the authors compared thirst and quenched states, they found distinct patterns of activity in the insular cortical activity. They also showed that these patterns were consistent across days, and that they could train a classifier to predict whether an animal was in a quenched or thirsty state. The pattern of activity across the population specifically was essential to differentiating between the states, as classification accuracy was poor when single neurons or the average population time-course was used. These results suggest that ongoing activity patterns in insular cortex represent distinct physiological states that reflect hunger or thirst.

The authors also demonstrated that task events, arousal and motion could only be predicted in a small set of insular cortex neurons, suggesting that the activity of the majority of insular cortex neurons do not reflect these factors. To confirm their findings in an independent sample, the authors also classified hungry versus sated (as opposed to thirsty versus quenched) states in mice with good classification accuracy. However, they could not predict hungry versus sated states when they trained the classifier on thirsty versus quenched states from another day. They suggest that ongoing activity in insular cortex may be different for hunger vs. thirst states. The authors found that artificial activation of thirst neurons during a quenched state restored insular cortex responses to water-related cues. Similarly, artificial inhibition of hypothalamic thirst neurons reduced insular cortex response to water cues. Importantly, however, when the authors analyzed ongoing activity during artificial thirst stimulation following behavioral quenching and rehydration, they found that insular activity did not resemble the thirst-like pattern. Critically, water cues and consumption of a drop of water in the dehydrated state transiently shifted the pattern of activity towards the pattern of ongoing activity observed in the quenched state, suggesting cues led to prediction of a future quenched state.

What's the impact?

The authors show that 1) ongoing activity patterns can discriminate between physiological states, and that 2) cues predicting availability of water/food may actually drive a prediction of a future satiety state in insular cortex. These findings deepen our understanding of interoceptive prediction, and will allow future studies to better understand interoceptive prediction errors.

Livneh et al. Estimation of Current and Future Physiological States in Insular Cortex. Neuron. (2020). Access the original scientific publication here.

In addition to Andermann and Livneh, authors included Arthur U. Sugden, Joseph C. Madera, Rachel A Essner, Vanessa I Flores, Jon M. Resch and Bradford B. Lowell, all of BIDMC; and Lauren A. Sugden of Duquesne University.

This work was supported by The Charles A. King Trust Postdoctoral Fellowship; Boston Nutrition Obesity Research Center P&F 2P30DK046200-26; grants from the National Institutes of Health (K99 HL144923; T32 5T32DK007516; DP2 DK105570; R01 DK109930; DP1 AT010971; R01 DK075632; R01 DK096010; R01 DK089044; R01 DK111401; P03 DK046200; and P03 DK057521); grants from the National Science Foundation (DGE1745303); Klarman Family Foundation; McKnight Foundations; Smith Family Foundation; and Pew Scholars Program.