The Role of Gut Microbes in Neurological Disorders

Post by Amanda McFarlan

What's the science?

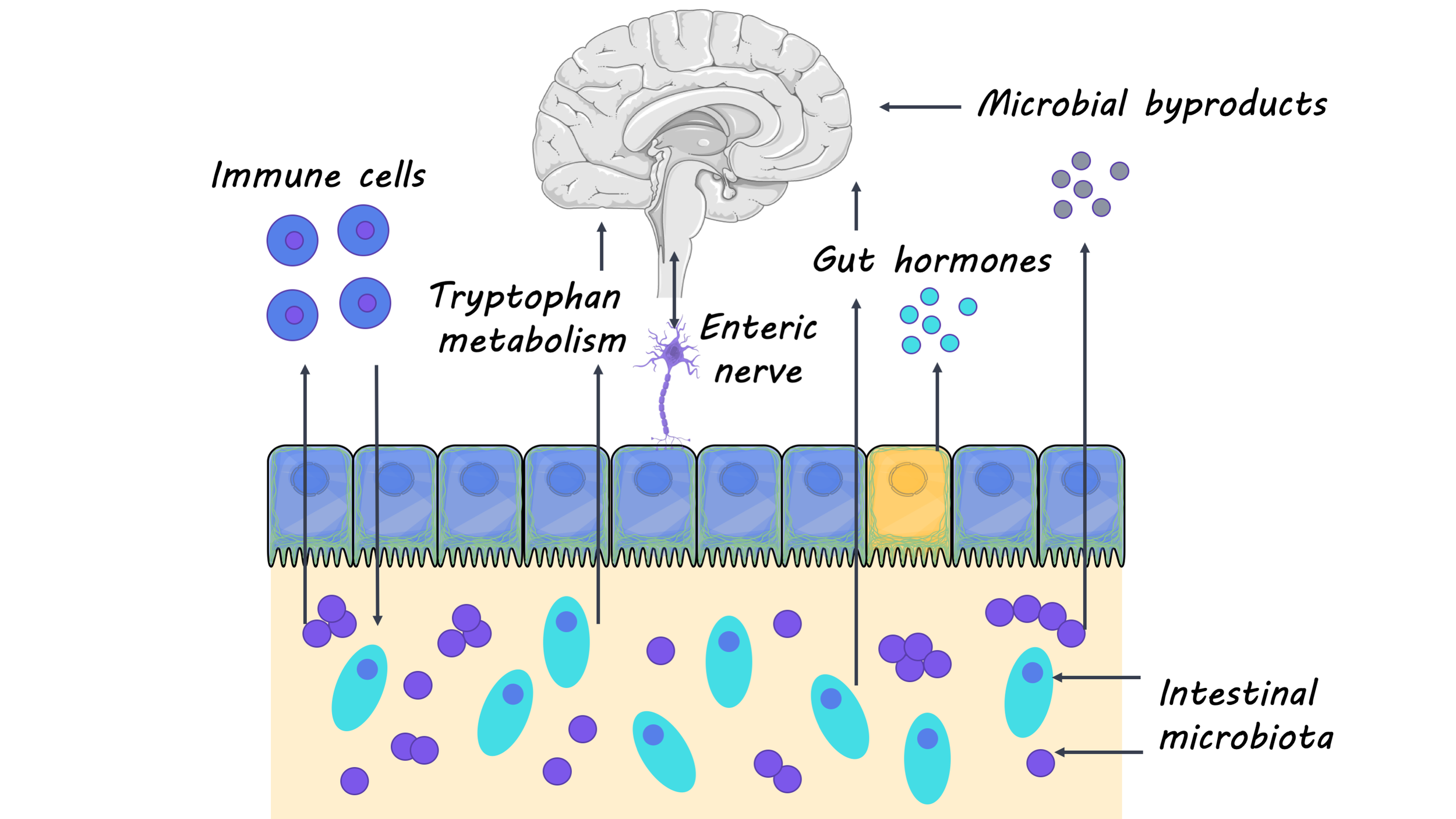

Research investigating the relationship between the gut microbiota (the ensemble of microorganisms in the gut) and overall health has gained increasing popularity in recent years. Studies have shown that the gut microbiota is important for regulating many major systems of the body, including the central nervous system. This week in The Lancet Neurology, Cryan and colleagues summarized past and present research that highlights the important role of gut microbiota in regulating the central nervous system.

What do we already know?

Much of our understanding of how the gut microbiota affects the central nervous system comes from studies using germ-free mice (i.e. lacking any gut microbiota). Researchers have shown that without the gut microbiota, germ-free mice have deficits in many neural processes that are critical for development and aging, including the maturation and myelination of neurons, neurogenesis and microglia activation. Additionally, germ-free mice had higher levels of neuroinflammation and an increase in the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, which are hallmarks of the immune-related neurological disease, multiple sclerosis. These studies with germ-free mice have provided researchers with important insights into how the gut microbiome is implicated in neurodevelopment, aging, and neurodegenerative disease. Researchers have continued to use animal models as well as clinical studies to further our understanding of the interaction between the gut and the brain.

What’s new?

In recent studies, researchers have focused on how gut microorganisms can be targeted for therapeutic purposes in neurological diseases. In the case of treating multiple sclerosis, for example, researchers found that a multispecies probiotic, administered two times a day for two months, had an anti-inflammatory effect and reversed changes in gut microbiota. Moreover, a clinical trial for children with autism spectrum disorder revealed that children who received a microbiota transfer had significantly reduced gastrointestinal problems (commonly found to be co-morbid with autism spectrum disorder) as well as behavioral improvements. These findings suggest that some gut microbiota may be a potential target for the treatment of neurological disorders. Additionally, researchers have started to look at how gut microbiota may regulate the physiology and behavior of neurological disorders like Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and epilepsy. For example, researchers found that the gut microbiota is involved in synaptic changes that occur in brain regions that are associated with epilepsy. They also found that the therapeutic effects of a ketogenic diet on epilepsy are dependent on gut microbiota. Finally, recent studies have shown that many non-antibiotic drugs influence gut microbiota, highlighting the importance of investigating the relationship between the gut microbiome and medications (especially those that are prescribed for treating a neurological disorder).

What's the bottom line?

The importance of gut microbiota on the development and overall health of the brain is becoming more and more evident. Studies with animal models and clinical trials have provided strong evidence for the role of the gut microbiota in neurological diseases like multiple sclerosis and autism spectrum disorder, with a growing body of research showing implications of the gut microbiota in many other diseases. Still, there is much more to be done in this field to elucidate the mechanisms by which gut microorganisms influence the brain. A better understanding of the gut-brain axis will provide insight into new therapies that may help treat or prevent a wide range of neurological disorders.

Cryan et al. The gut microbiome in neurological disorders. The Lancet Neurology (2019). Access the original scientific publication here.