Exploring the Neurobiology of Consciousness Using the Psychedelic DMT

Post by Flora Moujaes

What's the science?

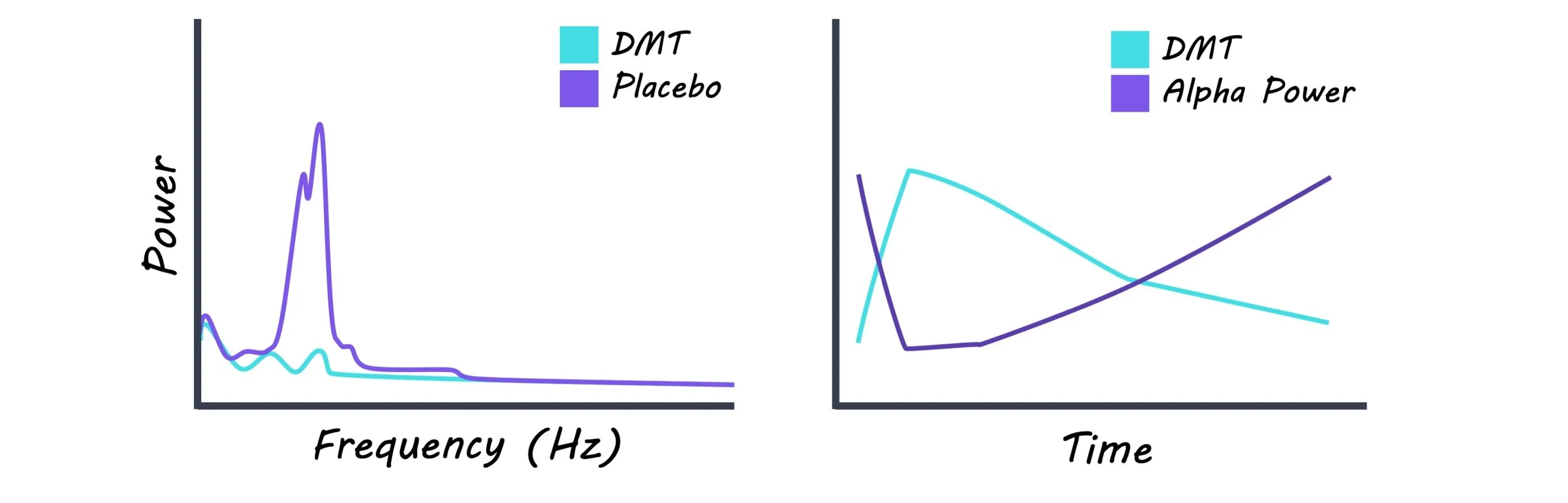

What is consciousness and what are the neural mechanisms that underlie it? We still don’t know the answer to these elusive questions. One exciting new avenue for studying the neurobiology of consciousness is to examine the altered states of consciousness produced by psychedelic drugs. For example, research has shown that LSD, psilocybin (the main psychoactive principle in magic mushrooms), and DMT (a naturally occurring psychedelic used in the ceremonial brew ayahuasca) consistently show broadband decreases in oscillatory power using EEG, particularly in alpha power (oscillations at approximately 8-12 Hz) which is linked to relaxation. Psychedelics have also been shown to increase the complexity or diversity of brain activity. DMT is a psychedelic of particular interest, as it produces one of the most unusual and intense altered states of consciousness, and has previously been likened to both dreaming and the near-death experience. This week in Scientific Reports, Timmermann and colleagues conducted the first ever placebo-controlled investigation of the effects of DMT on brain activity in humans at rest.

How did they do it?

To examine the effects of DMT on the brain at rest the authors collected EEG data on thirteen participants during a placebo session first and a DMT session a week later. Placebo or DMT was administered intravenously. The authors collected EEG data starting one minute prior to administration and ended 20 minutes post administration. Blood samples were collected at regular intervals throughout the EEG sessions. Three types of subjective effect measures were collected: (1) participants were required to give a real-time intensity rating of the subjective effects they experienced once every minute, (2) participants completed Visual Analogue Scales once the subjective effects had subsided, (3) the next day an independent researcher conducted a micro-phenomenological interview, designed to reduce subjective bias in first-person reports.

What did they find?

The authors’ primary hypothesis was that DMT would decrease oscillatory power in the alpha band and increase cortical signal diversity and that these effects would correlate with changes in conscious experience over time. Overall, their results support this hypothesis, as the authors found strong correlations between alpha and beta power decreases, real-time changes in the intensity rating of subjective effects of DMT, and DMT levels in plasma. They also found increases in delta and theta oscillations, which emerged during the peak of DMT’s effects. These findings suggest that the emergence of theta/delta rhythmicity combined with suppression of alpha/beta rhythmicity may relate to the ‘DMT breakthrough experience’, where the brain switches from processing external information to a state where processing is internally driven, which is also characteristic of dreaming during REM sleep.

DMT immersion also led to widespread increases in signal diversity which correlated with real-time changes in the intensity rating of subjective effects of DMT, and DMT levels in plasma. This is consistent with the ‘entropic brain hypothesis’ which proposes that within a limited range of states, the richness of content of a conscious state can be indexed by the entropy, or complexity, of spontaneous brain activity.

What's the impact?

This study is the first ever placebo-controlled investigation into the effects of DMT on brain activity in humans at rest. The finding that DMT results in decreased spectral power in the alpha/beta bands and widespread increases in signal diversity, both of which correlate with the subjective intensity of DMT’s effects, indicates that more work is needed to better understand how these findings relate to the neurobiology of consciousness. This study can also shed light on the mechanisms underlying DMT’s antidepressant effects, as depression has been linked to increased alpha power. Overall, this study advances our understanding of altered states of consciousness.

Timmermann et al. Neural correlates of the DMT experience assessed with multivariate EEG. Scientific Reports (2019). Access the original scientific publication here.