Driving Brain Plasticity with Gamma Oscillations

Post by Anastasia Sares

What's the science?

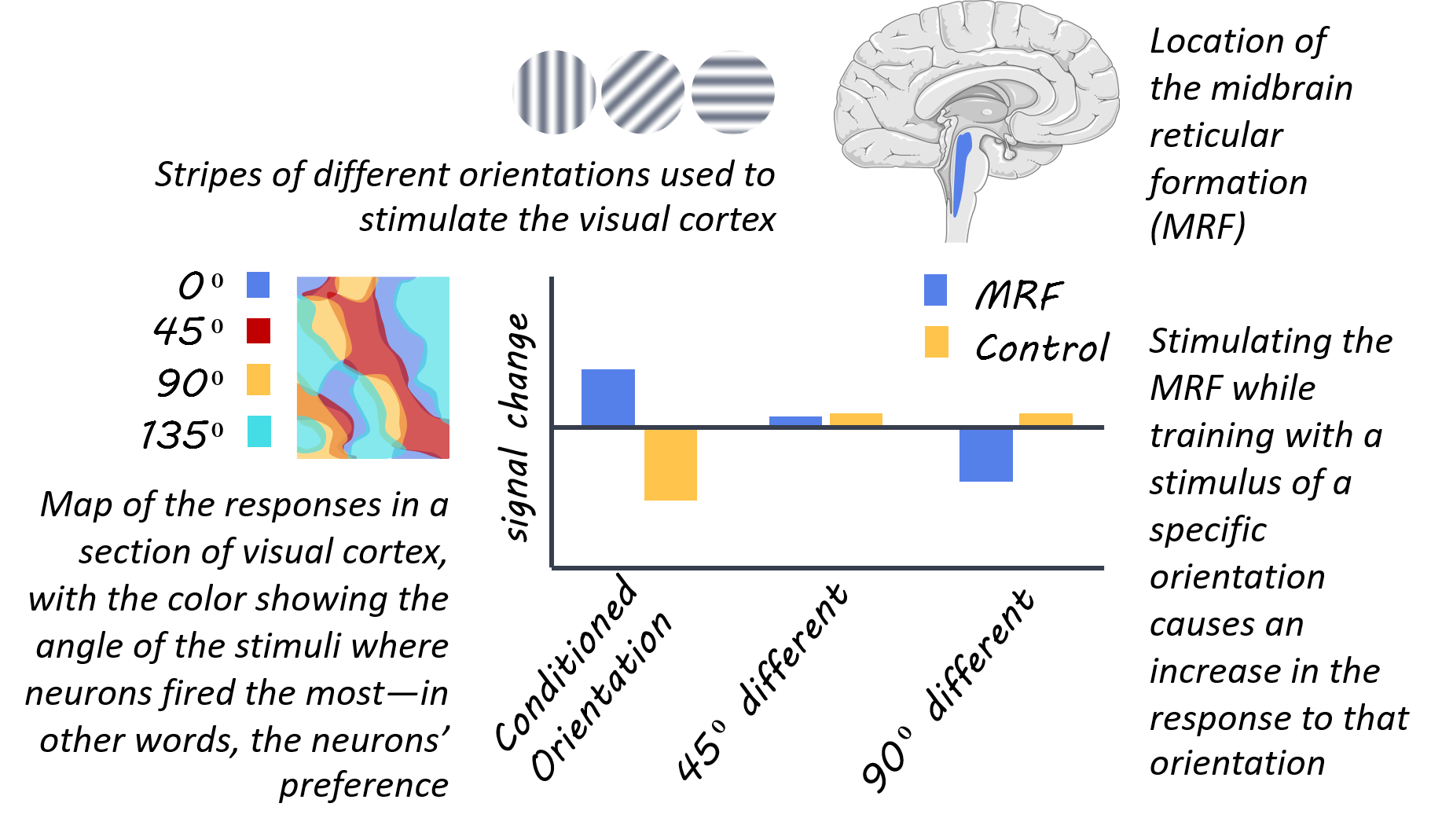

The visual cortex is a classical area for studying neuron tuning, specialization, and brain plasticity. Located in the very back of the brain, the visual cortex was studied as early as the 1960s, and it was discovered that different clusters of neurons responded to moving stripes oriented at different angles. Changing the preferred orientation of some neurons is a small-scale example of brain plasticity, but it doesn’t happen all by itself. Something has to happen in the brain to change the status quo. This week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Galuske and colleagues induced brain plasticity by pairing visual conditioning with stimulation of a brainstem area (midbrain reticular formation).

How did they do it?

The authors studied the visual cortex of cats, implanting electrodes in order to record neural activity (more specifically: electrocorticograms, multiunit activity, and local field potentials), and also performed optical imaging. They recorded neural responses to different orientations of stripes to create an “orientation map” of the cortex. Recordings took place before and after a long conditioning session, where the cats were exposed to moving stripes (also called ‘gratings’) in a single orientation. Repeatedly exposing neurons to the same stimulus (stripes at a certain orientation) usually just causes them to habituate, firing less as they get used to the stimulus. It does not typically change their preferred orientation. However, during some of the conditioning sessions, the authors additionally stimulated the midbrain reticular formation (MRF) in the brainstem. Activity in this brainstem area can enhance gamma oscillations in the visual cortex, which the authors believed would drive plasticity. This plasticity would cause greater responsiveness and attunement to the orientation presented in the conditioning session.

What did they find?

The authors succeeded in causing a plastic change in the visual neurons. After the conditioning session with the MRF being stimulated, more neurons responded to the grating that had been presented. The cells that changed the most were the ones that had originally responded to orientations 10-30 degrees away. These cells were “re-tuned” so that they preferred the orientation presented in the session. The effect lasted at least 6 hours, at which point the researchers stopped measuring it. It wasn’t just stimulation of the MRF that caused this plasticity. Only when MRF stimulation led to an increase in gamma oscillations did this effect show up.

What's the impact?

This study shows that gamma oscillations put the brain’s cortex in a unique state that facilitates plasticity, changing how it represents the outside world. More research is needed to connect gamma oscillations to learning, but some evidence suggests that they may be related to context and prediction, providing a way for the brain to turn plasticity on or off when the need arises.

Galuske et al. Relation between gamma oscillations and neuronal plasticity in the visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2019). Access the original scientific publication here.